Translated by Lola Malavasi

They say that near the Nuclear City, another settlement has arisen. A place with its own rules and ways of coexisting with other surrounding areas, other ecosystems, other natural instances where birds, insects, reptiles also abound… Because in that place, life resumed when humanity stopped doing its thing. They say that cattle graze there, that farmers sow in silence to trade and eat. They say brackish and sweet waters flow there, making children, elders, and fish happy. They say people often live on the margins, even outside the law. They say this place has no name because words as we know them are part of a particular official system not shared here. We need to exercise and/or reformulate other ways (new or old), affective or effective, of approaching, knowing, and interpreting it. They say this astonishing, unprecedented landscape emerged after the fracture of a great project, something unfinished to this day, more than forty years later. The atomic and immeasurable desire of an island. The overflowing eagerness of a man, the dream that escaped his reach…1

This is the story of a place told by the things that happened, by the people who inhabited and still inhabit the space. But also by the places they never got to know and nevertheless persist as an insomniac memory. There, the past, present, and future intertwine with fiction, with the margins of the possible, with unfulfilled promise, illusion, and failure, with resilience and uprooting. Objects, sounds, planes, machinery, sensations that converge beyond imagination and memory.

That Work of the Century

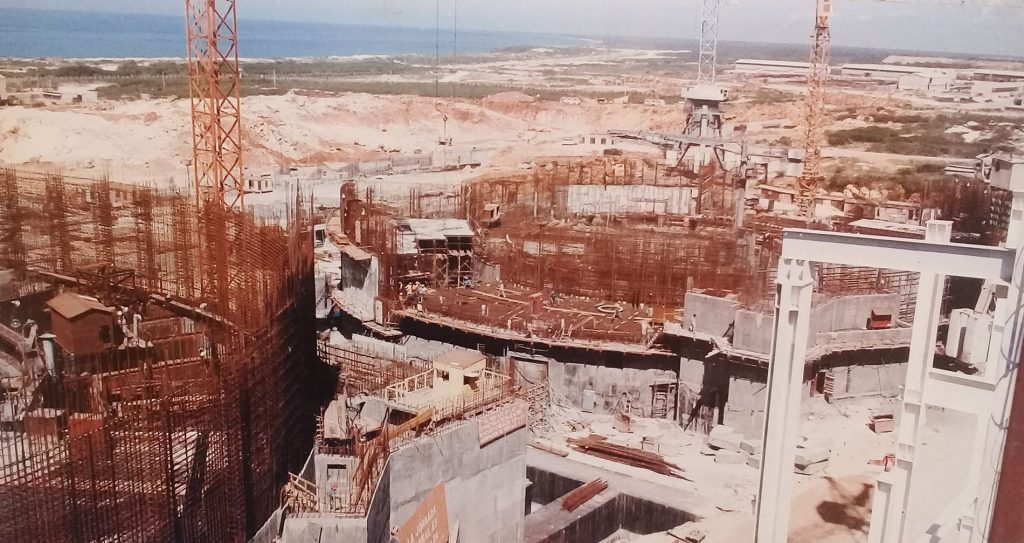

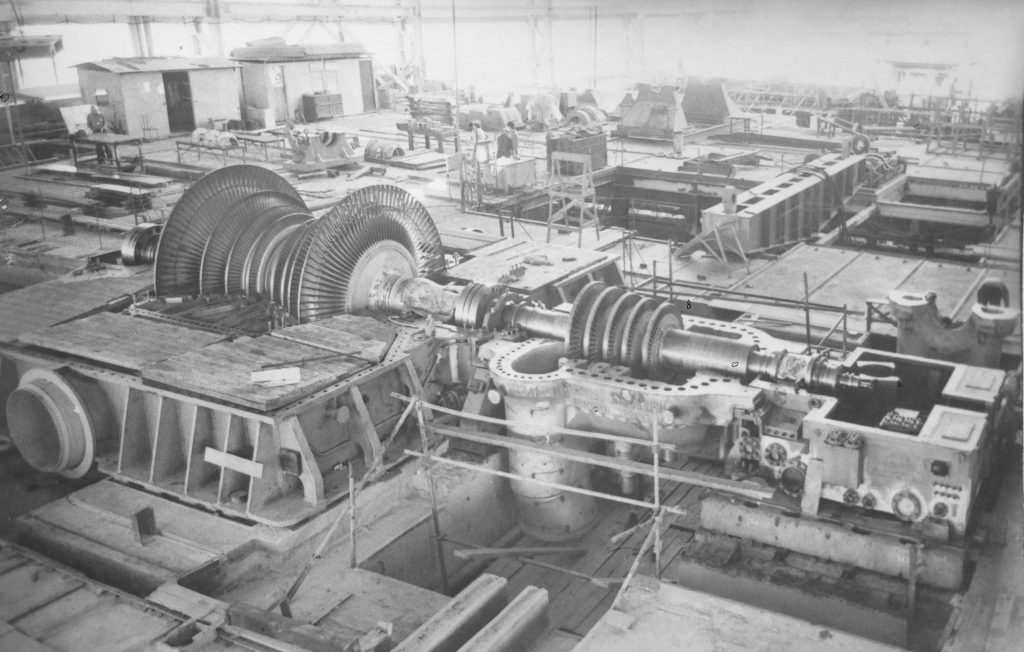

The Juraguá Nuclear Power Plant (CEN by its acronym in Spanish), located in the municipality of Abreus, Cienfuegos province, was the most ambitious industrial project of the Cuban revolution. Not only did it represent the promise of an energy future but the consecration of socialism on the island as well. Work began in 1982 with Soviet financing and supervision. In principle, the agreement was to build two VVER-440 V318 reactors. The project was born in 1974, following President Fidel Castro’s visit to the nuclear power plant of Novovoronezh on the banks of the Don River, where many Cuban scientists were studying.

The plant’s objective was to supply up to 15% of the country’s energy demand and to be a source of jobs. Hence, parallel to the plant, the construction of the Nuclear City began. This settlement included housing and infrastructure to house the project workers —many of whom came from the USSR— as well as the future Cuban workers and their families. This “wonder city” was located a few kilometers from the future CEN in an area where before there had only been vegetation, local animals, and Castillo-Perché, a former fishing settlement nearby.

But the “work of the century,” as Fidel Castro himself called it, was halted ten years later, in 1992, after the fall of the socialist camp and the USSR, as well as increased pressure from the United States.

One reactor was 75% complete at the time, and the other was 25%. The engine room and other buildings were also in an advanced state. The cost of lives and resources was vast. All this, coupled with the arrival of the Special Period, one of the most terrible economic crises the country has ever gone through, brought about the need for Cuban personnel to reinvent themselves and find new ways to survive.

During the following years, there were several attempts to restart the works, but it proved impossible.

Like the plant, the Nuclear City remained half-built. Over the years, a veil of silence and concealment fell over both projects. They were the living image of the failure of economic and political utopias. Even today, talking openly about the subject is taboo in certain circles on the island.

Micropolitics of the City and the Landscape

Utopian cities and the overflowing desires represented by monstrous engineering constructions are paradigms that concentrate the longings of a person, a society, or a country. It is the point where a world vision, a vision of life, gathers and densifies. In this case, a failed nuclear project.

I have been collaborating since 2017 with a group of artists, activists, local scientists, and from other parts of the island in creating actions2 that aim to connect art, community, and the environment. These actions address the history, reality, and future perspectives of the inhabitants of the Nuclear City and its surroundings. They rely on various practices such as performative writing, audiovisual production, photography, music, and others, that have been crucial to trigger reflection and collaborative work.

The people of the Nuclear City and Castillo-Perché have an enormous potential to be thought of, re-signified. Because of this, our desire as artists and researchers is to work from the micro-political, from the life that happens every day —human, vegetable, animal—, from the ruins of the reactor that dominate the landscape.

Our purpose has been to go into the fissures, the ruptures, the ruins where the layers of different eras meet and coexist. It is precisely from there that we have carried out actions with the objective of listening and reinventing the “territory” (from the experiences of its inhabitants and even our own) in the hope that they will continue to resonate later and contribute to a better understanding, sharing, and connection with the space.

When we think of those interstices, those fissures, those cracks, we understand them not only in the physicality of the place but also in the layers of history(s) where those imaginaries continue to coexist. There is something important not only in what no longer exists: a city, a reactor, a monstrous work but also in the possibility of overflow. Not only of what was or is, but of what could happen. Is it possible for a reactor lost under weeds and oblivion to mutate into something else? Is it possible for history to repeat itself? Is it possible to contain an imminent catastrophe?

Living Near a Myth

Why does this “city” feel foreign? Why is it so hard to put down roots here? When was the last time you thought about not leaving this place? The residents of Nuclear City and the surrounding area are sure that the proximity of an unfinished reactor is not a random event. Living near a myth is far from being a casual fate.

Since the beginning of the CEN, many people have passed through here. “The first to arrive were the Bulgarian builders, from the Venceremos brigade, in 1975. Then the Russians joined in, whom no one called Soviets, but Russians,”3 Olga told me a few years ago. Olga was a cashier at the supermarket where Russian families shopped. During that time, about two thousand people from the Soviet Union lived with the Cubans. However, when the project stopped, everyone began to leave. Olga worked with the family of one of the supervisors, who stayed until the end of the dismantling of the facilities. They were the last to leave.

However, in this area of the Abreus municipality, a settlement had already existed for more than three hundred years. In the 18th century, the Spaniards built a system of fortifications whose center was the Fortress Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles de Jagua. The movement that resulted from this construction attracted labor that settled in this place and began to be identified with the name of the construction company: Castillo de Jagua.

The people of Castillo-Perché currently have a great fishing tradition. This is their main means of income. They also make charcoal ovens (fuel used to prepare food), which have been a useful source of income after the increase of the economic crisis in Cuba in recent years. This community has a strong sense of belonging. The local language is marked by maritime identity. They also enjoy a rich oral tradition related to fishing, culinary art, tales, myths, and legends. Castillo-Perché borders the Nuclear City and is located very close to the CEN.

“The ‘seafarers’ are different from ‘mountain people.’ The ‘mountain people’ arrived all at once as the buildings arrived. It has been a difficult relationship. It took time, even blood,” said Atilio Caballero, director of Teatro de la Fortaleza, a group that has lived in the area for more than eighteen years.

When work on the plant stopped, most scientists, engineers, and qualified personnel who lived in the Nuclear City moved to other parts of the island. Little by little, people from the East of the country arrived in search of economic improvements. Many of them had no formal education and were trained in hard work. Some stayed for a while and then moved elsewhere. This was the beginning of a demographic displacement that is still noticeable today.

All of what has been mentioned, in addition to the historical neglect suffered by the Nuclear City, has favored a double marginalization: external and internal. This situation has had impactful sociological consequences: the increase of gender violence, machismo, homophobia, and transphobia, as well as the constant migration of young people, something that has increased enormously in recent years.

The Reality That Contains Us

Although the Nuclear City lacks an initial cultural infrastructure (cinemas, theaters, leisure centers), some local centers and institutions, such as the Casa de Cultura CEN Luis Romero, have developed socio-educational actions involving the community that have been effective tools to promote inclusion and social cohesion.

I would also like to mention Teatro de La Fortaleza, a research center and workshop for training and theatrical production. Not only is it inspired by issues and problems of the CEN, but is itself an act of artistic resistance, maintaining its headquarters and daily practice there for almost two decades. Teatro de La Fortaleza has been recognized nationally and internationally thanks to its participation in numerous festivals and events.

In general, the work of these entities with children, adolescents, and young people has been decisive in exploring cultural identity and developing social and emotional skills. Promoting music, dance, theater, and literature has fostered self-expression and a sense of belonging to the environment. The participation of adults who, for example, were linked to the CEN and in whom apathy, distrust, and lack of faith abound, has been a way for them to stay active and share their life experiences and knowledge with others.

However, although these initiatives have been very important, they are not enough to address other latent problems, such as gender violence, machismo, homophobia, and transphobia. For this, it is vital to involve other entities, local and regional, to advise and accompany the community, which would be an incentive to create a safer and more supportive environment for all its members.

Finally, I would like to mention some works that in recent years have made visible on an international scale the mysticism of this place and the stories of its inhabitants. Among them are the feature film La obra del siglo (The Project of the Century), directed by Carlos Machado Quintela; the short film Natalia Nikolaevna, by Luis Alejandro Yero and Adrián Silvestre; the documentary Bretón es un bebé (Breton is a baby), by Arturo Sotto, among others. As well as Franjas, by novelist and theater director Atilio Caballero, and the poetry of Katherine Bisquet in her book Uranio empobrecido.4

Crossing the Blue Waters

How do we position ourselves before the reality that contains us? How do we inhabit the responsibility of urban space and sustainability within the relationships they create with their environment? How do we commit to act against this information we are not allowed to know and participate in? Is it possible for a reactor lost under weeds and oblivion to mutate into something else? Is it possible that history repeats itself?

When the CEN was shut down, the surrounding ecosystem grew and regenerated. The flora gained ground. Groundwater (abundant in the region) invaded the built-up areas. The surrounding lands were taken over by farmers, who also brought their animals (cows, pigs, goats). Today, these are even areas inhabited (not always legally) by people who migrate from the East of the country in search of better economic possibilities. During the last three decades, an entire marine and terrestrial ecosystem of human, animal, and plant life populated and settled the area, covering the ruin left by the large industrial structure. Today it is an environment that extends solidly into the surroundings of that construction. However, all this could be about to change.

In December 2015, the Cuban government announced through official media the implementation of a national confinement of toxic waste in the facilities of the former Juraguá nuclear power plant. The news, moreover, appeared within the National Environmental Strategy 2016-2020 of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment. However, to this day, it has not been possible to corroborate that the members of the surrounding communities have had access to updated and regular information about this project.

Often, the germ of one process is the continuation of another. Often, the objective of sharing a question or a problem with others is to find paths in which research leads to other/new spaces that translate this question or problem into processes that generate their own path, becoming sequels of that primary gesture.

The initiatives deployed during these years have also focused on fostering links between the inhabitants of the area and their natural environment. Our interest has been taking the work done in academic research and by specialists in scientific branches to try to enrich them through local knowledge and participation. All this is done taking into account who they are, how they feel, what place they have in this micro-world (say, Ciudad Nuclear, Castillo-Perché, etc.), and the systems of relationships that are established between them and the landscape that surrounds them daily. Hence, although the projects are born from working with the intimate and the biographical, they slowly become part of the community and the context, serving as materiality to build new stories that alter the official narratives.

Our desire has been to include all voices and all bodies with their habits, dynamics, and individual interests, as well as to ask and listen to each other as participants in this small universe. To create alliances with the territory that allow us to share common stories with other people, other cities, other ecosystems, other paths, other blue lakes born after the collapse of a utopia. Our desire has been to inhabit the register and safeguard the memory of the project so that they become detonators of other individualities, processes, collectives. To live a time and a space putting aside even words, to communicate in other ways, to reveal something in this path, not a great truth, but a desire.

They say that near the Nuclear City, another settlement has emerged. They say there are roads to reach it, although most are lost amongst the weeds. The maps don’t show them. The maps we know do not know how to see. They say cattle graze in that place, that farmers sow in silence to trade and eat. They say that the neighbors use the vegetation sites and former spaces for industrial use as places for recreation. They say this amazing, unprecedented landscape cropped up after the fracture of a great project, something still unfinished after more than forty years. The immeasurable desire for an island. The overflowing eagerness of a man, the dream that escaped his reach. The beginning of a journey that has not yet ended.

Welcome.