The congonhas and the whispering mountains

by: Walla Capelobo

Brazil, Climate Justice, Extractivism

Translated by Lola Malavasi

“Shine bright like a diamond”

Rihanna

Part I

I forgot about you and I remembered myself

Às Congonhas e às montanhas que sussurram (The Congonhas and the whispering mountains) is a work that sprang from my intuition and curiosity about the congonhas, an autochthonous plant of the Brazilian Cerrado, with twisted stems, thick leaves, and roots that deeply penetrate the rocky and iron-rich floor. Aside from giving its name to the city where I was born, in the interior of Minas Gerais, Brazil, congonhas are a source of healing and mysteries, which stimulated my desire to get to know them better. Given the abundance of this plant in the region’s stony fields, the Portuguese colonialists named the small valley in the center of what would later become Minas Gerais Congonhas. Today, the congonhas belong to the immense list of endangered species. Their disappearance is directly proportional to the increasing destruction of the landscape by mining. Since the 17th century, Congonhas has suffered the consequences of having soil rich in minerals. During the official colonial period, gold was the first thing to be turned into merchandise. This event created the first waves of ecological destruction in this locality. As I write this, the Congonhas area is undergoing another cycle of expropriation: since the 19th century, and with greater intensity since the 1940s, iron ore has been intensively exploited. The region is called the Iron Quadrilateral and is home to one of the largest iron deposits on the planet, the wealth of which will soon be exhausted. I write on the soil of one of the regions that suffers the most from environmental crimes and their social consequences; crimes such as the rupture of the iron tailings dams in Mariana (2015) and Brumadinho (2019), work accidents, extinction of plant and animal species, as well as constant violations of human rights. These are some of the everyday realities in places mined by companies such as Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional and Companhia Vale do Rio Doce, in addition to the policies of the state of Minas Gerais and the Brazilian government that “legalize” the assault of territories and our bodies. Argentine researcher Horacio Machado Aráoz asserts that “…modern life is inconceivable without mining. In its evolution and in its present, Modernity is integrally a complete mineral experience.”1 Further on, he states that “Western civilization has mineralized the human condition,” that is to say, mining, a primordial phenomenon in the world’s colonial mode of production, has created a condition of existence in which human and non-human beings can be expropriated from the Earth until their exhaustion or extinction.

Despite having lived for years in the territory of Congonhas, I did not know the magical plants from which its name derives. And yet, I dreamed of the day I could establish a relationship with them. The mode of existence that the ordered world produced through modern/colonial logic —as Denise Ferreira da Silva argues— is composed of a set of operations based on fragmentation (Cartesian), sequentiality (linearity of time), and determinability. Denise calls this set of procedures the epistemological pillars of modernity,2 actions that constitute the maintenance of the world as it has been made known to us.

My work is also born out of the desire to destroy this world besieged by modern/colonial logic, where its sustenance is only possible through the act of dispossession of indigenous lands and the perpetuation of the processes of enslavement of dark people (pretes africanes, Afro-descendants, and humans of the invaded lands). For decades I have witnessed an extremely intense force fragmenting the mountains. I have never gotten used to such destruction. I feel the extreme extractive force of minerals in my life and in the lives of family members who work in the service of extraction (my father, my mother, my brother, uncles, aunts, cousins, and my paternal grandfather), as well as the community around me (neighbors and friends) whose souls reveal the symptoms of a stratified life. My work is a way of redistributing violence,3 not just a complaint, but a way to explain and share what I feel and live, beyond the individual problem, as part of a web of dark lives fragmented by the colonial system.

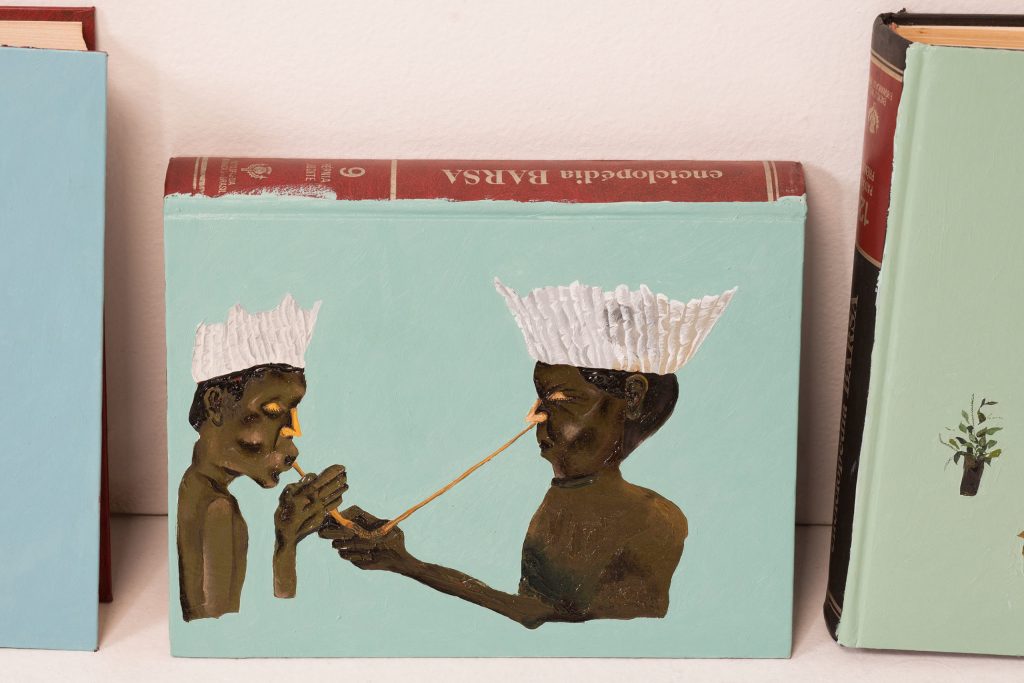

Dalton Paula, an artist I admire greatly, was a big inspiration for me during the process of making Às Congonhas e às montanhas que sussurram. Her works As plantas curam (Plants Cure, 2016), A cura (The Cure, 2016), and Santos Remédios (Holy Remedies, 2016) present healing routes for those of us who do not feel safe in invaded lands. The artistic procedures of Castiel Vitorino, also Brazilian, particularly in Room for Healing (2018), nourished my Orí in the paths of the congonhas. Both Dalton and Castiel construct the cure for the ills of the Brazilian sickly system through non-westernized procedures, knowledge sustained not in modernity/coloniality but in complex matrices of knowledge that survived the Brazilian project. Some of the procedures present in these works, in my body/life, and in my creative gestures are ancestralities (the origin of which is the earth and Africa), orality, the so-called popular wisdom, spiritual communications, capacity for dialogue with non-human beings, rejection of humanity modulated by whiteness.

Two years ago, I began a conversation with the congonhas. My paternal grandfather, Expedito Teixeira, introduced us. He is one of the only people in my family that knows of the congonhas and their effects. After many years mining in Morro do Chapéu (Nova Lima, Minas Gerais) he amassed grassroots knowledge of the Brazilian Cerrado. He talks to us about the explosions that destroy the landscape in seconds from experience. He also tells us about animals that we have not seen for decades, plants that I only know through his voice, springs that have dried up, and how congonha tea used to be present in the community’s daily life.

With his guidance, I walk through the forests of Congonhas, through the hills of Pires and Casa de Pedra, to experience beings that were taken from us. Looking for the congonhas, I found a forest. Every day that went by without finding them, my senses awoke to other worlds that existed beyond mining. Stories, encounters, and conversations with the rivers Maranhão, Soledade, Paraopeba, Camapuã that surround the mountains with their mysterious waters, capable of shouting among the silences of extinctions. The mountains, the cycle of the stones; when I lean on the iron, I am reminded of its presence in the center of the planet and I feel the honor of having it accompany me. The forests, sinuous trees, twisted and rigid, spread their roots on the rocks: jatobás, espinheiras, venenosas, frutas do lobo, tamarinds, plums, so many names and flavors that I would not have come to know without the paths opened by the congonhas. I came to understand the congonhas as a teacher plant, an elder plant that taught me cycles and paths, the strength necessary to sprout deep in the rocky soil. The congonhas enchanted my gaze. I began to see the multiple species that always surrounded me. How come I had lived all my life here without knowing this little corner of the forest? I began to know myself, lose myself, break down hallucinating and dreaming.

In February 2021, during a walk in the mountain range of the stone houses, I was surprised by a lightning discharge for the first time. I found, recognized, perceived, the congonhas. The other times I had seen them had been thanks to someone else. The community around me knows about my work, so it became common for people to show me, gift them, or tell me about the congonhas. When I recognized them in the forest, I felt like I had broken time. I felt the joy of embodying an impeded knowledge, glimpsing the impossibilities of forgetting. This encounter with the congonhas came to my mind during the course “Pensamento preto contemporâneo brasileiro, por um devir-quilombista das artes” (Contemporary Brazilian black thought, for a becoming quilombista of the arts), taught by Jorge Vasconcelos as part of the the Programa de Pós-Graduação Estudos Contemporâneos das Artes of the Universidade Federal Fluminense. The multidisciplinary artist Carmen Luz was part of this course. Carmen spoke generously about justice as an explosion, an event, a feeling closer to joy, and not a permanent state of things. I was moved by these words that led me through memory’s territory toward the encounter I had with the congonhas. That day I experienced justice, the thunder of joy that explodes and transforms. The justice of not forgetting. Our dark lives are impregnated with fiery volcanic explosions of justice. Since then, I desire moments of joy, of justice.

I became a ceramist during the process of Às Congonhas e às montanhas que sussurram. I found clay in the spiral of destiny. I was attracted to the clay’s red color, which I now know comes from iron. In 2020, I made Lameado: intuições e percepções da lama (Muddy: the intuitions and perceptions of mud) together with Elton Panamby and Verde, artist friends whom I deeply admire. We composed this film dedicated to mud through our coming together. We exchanged the sensations we experienced in the mud house,4 mangroves, swamps, ancestors, continuities, and the ways to preserve them. Since graduating from Art History at the Escola de Belas Artes of the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (EBA/UFRJ), I became interested in the arts of and about the earth. I came close to the practice by taking ceramic courses at the faculty of sculpture of the Escola with Professor Kátia Gorini. My encounter with cave paintings and ceramics of a time before the colonial period takes form in confections of continuities in which I destroy linearity by realizing that the clay I mold and in which I am molded is the same; we tremble in time.

Beatriz Nascimento and the knowledge from the quilombolas are woven within my adventures with clay because of their contributions about the quilombo as an entity of the earth, an agent of memory, a civilizing project, a principle, and a form of reconnecting with the ancestral forces. With clay, I experience what the quilombola leader Antônio Bispo says about the experience of life integrated into the earth, the wisdom inherited from African knowledge, the deep and dark relationship with the cosmos where the confluence of movements shapes the experiences. In an interview to which I had access through a fragment shared via Whatsapp, the Blessed Mother of Yemanjá speaks about the possibility of giving birth with one’s own hands, of the creative force of conception that dwells in the waters of our bodies. My sister and companion, Millena Lízia, shared with me a text in which Mãe Stella de Oxóssi narrates the importance of being at the bottom of the well where there seems to be no way out because it is from there that the force of fertility is born. With clay, I have managed to conceive worlds that cannot be determined in any instant. It is in the fire of the hours where the necessary transformations happen. It is up to me to accept them.

“The purpose of the seed of the earth is to take root in the stars.” This quote is from Lauren Oya Olamina, a character in the Parable Series5 by Octavia Butler. I have been learning a lot from Lauren and Octavia about the purpose of imagining the unforeseen for our dark lives. I have been giving shape and illuminating justice, healing, and an escape from extinction. It is a promise: we will not be driven to extinction. We will never be forgotten. The congonhas will sprout.

…