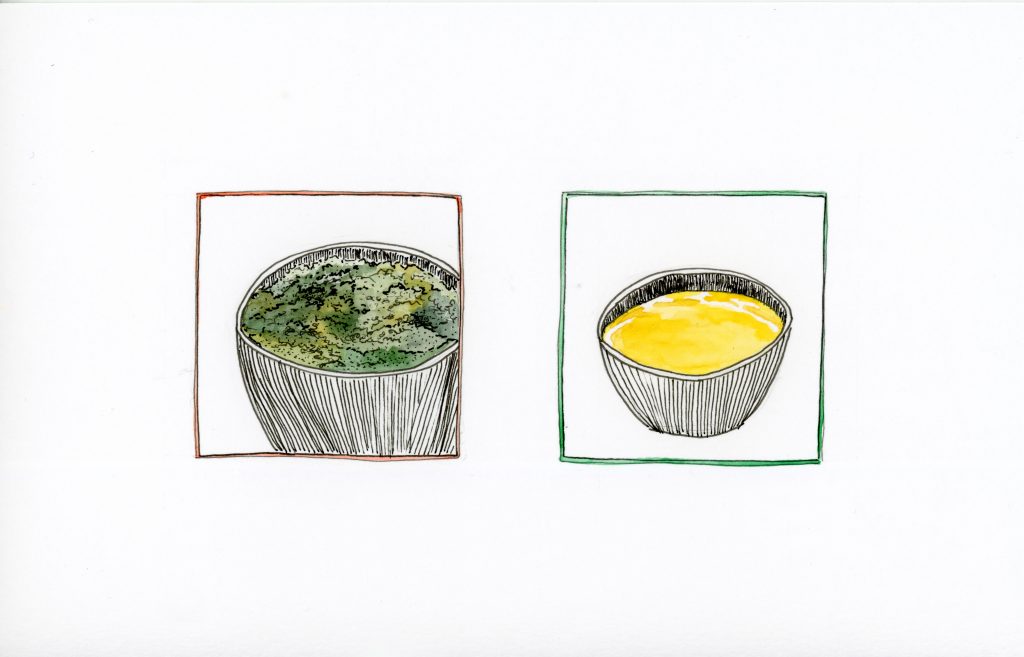

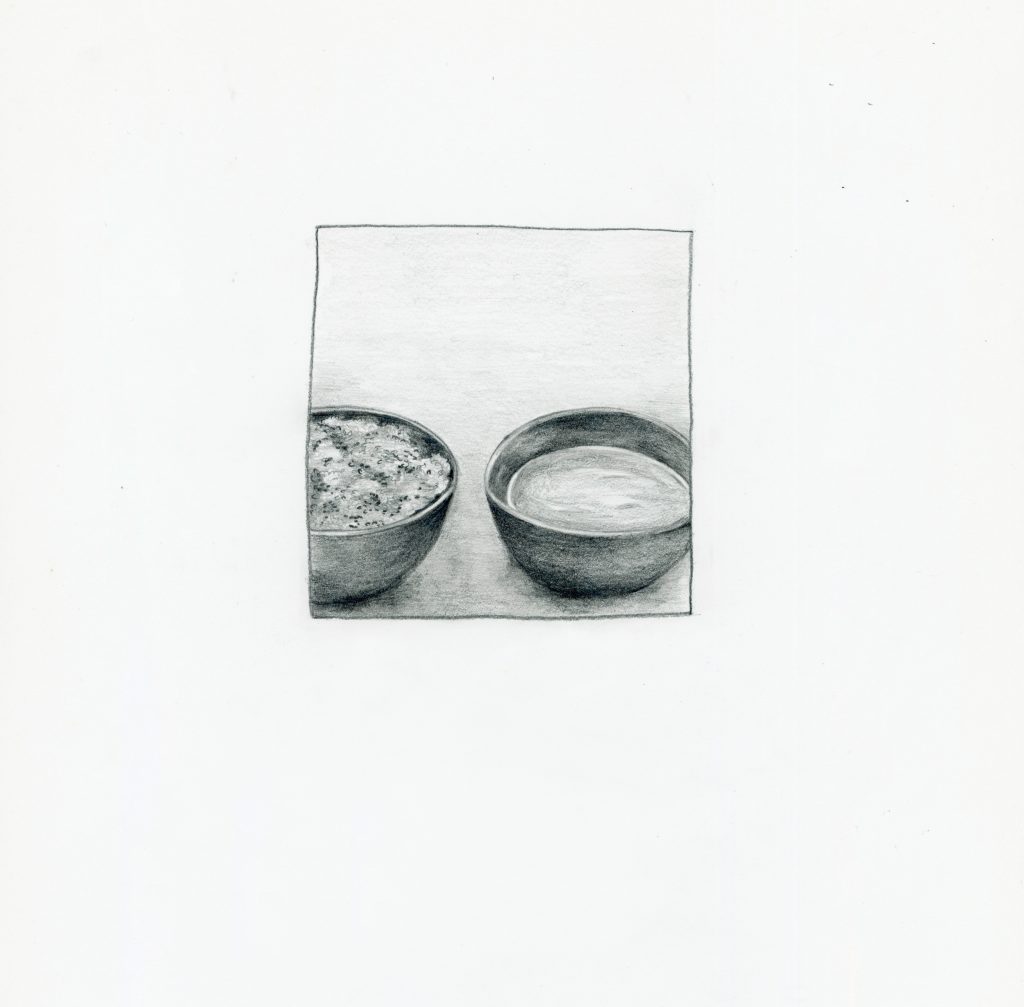

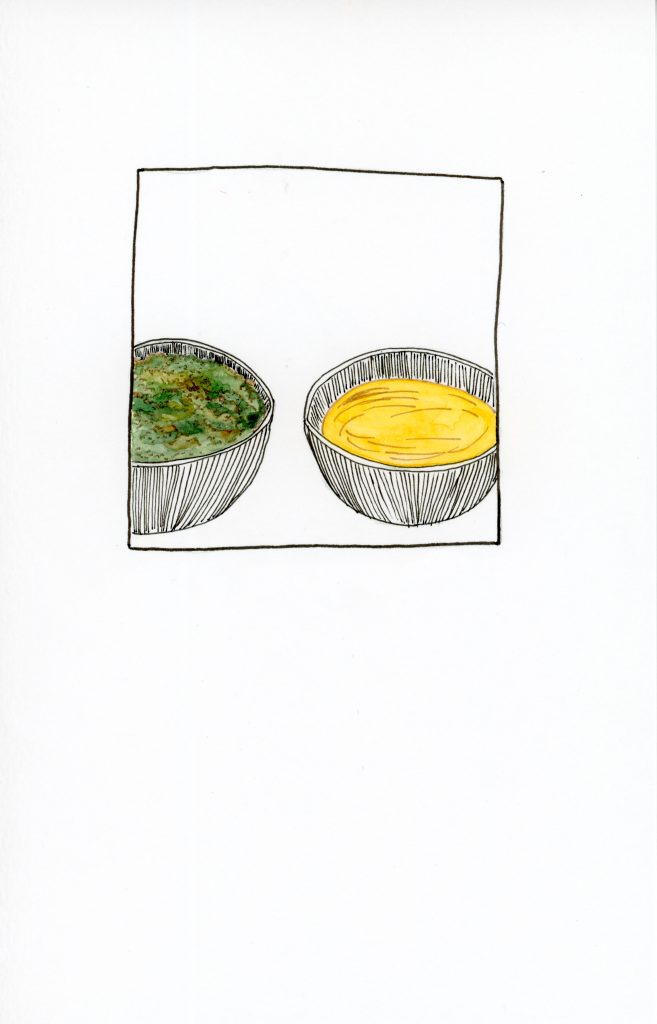

Za’atar and oil

by: Paula Piedra

Free Palestine, Palestine, solidarity

Paula Piedra in conversation with Zuhra Sasa

Illustrations by Viviana Zúñiga Ramírez, Translation revised by M. Paola Malavasi L.

At 5:00 p.m. on Monday, December 4, 2023, Zuhra opened the door to her apartment in Los Yoses, San José (Costa Rica). While she finished talking to a student via video call, Jengibre and Cúrcuma, a pair of feline siblings, ran to greet me. They kept me entertained until the moment she finished her virtual meeting. We greeted each other again and she immediately began preparing some food while we poured ourselves a glass of wine. Before she sat down at the table to talk to me, she brought some textiles of Palestinian origin. I had asked her to talk about a memory related to Palestine or her family, a memory that could be represented by a photo, an object, a song, a poem, or anything else that linked her to her Palestinian ancestry.

Zuhra Sasa Marín is an architect specializing in urban design and is the current director of the School of Architecture at the University of Costa Rica. Zuhra’s father was Abdulfatah Sasa Mahmoud (1940-2023), a Palestinian physician and activist who migrated to Costa Rica in 1973 with his Costa Rican wife, whom he met in Spain while they were both studying at the university and four of the five children they raised. At some point, Abdulfatah became a naturalized Costa Rican. But he never forgot where he came from and never stopped fighting for the Palestinian cause.

The following text is the result of a conversation with Zuhra. I omit my questions and interventions and share only the words she said to me on that windy December afternoon, in which Jengibre and Cúrcuma casually moved around the table as if wanting to catch the words we were saying so that they would not be blown away by the wind.

i. Rootedness to the land

I share with you these elements that symbolize Palestine for me. I think that the expression of the Palestinian textiles and what little Palestinian food I can offer you today represent, at least for me, that link that the Palestinian people have to their land, to the land they knew or have never known.

The olive tree, olives, and olive oil permeate their entire culinary culture.

Za’atar and oil, such a simple thing: oregano, sesame, and a little bit of sumac, a spice found in the Middle East. Such a simple thing is not just the basis of the culinary culture but of the Palestinian identity’s bond to their land. There is a very close relationship between the land, the olive tree, and the production. In my view, the Nakba, the first forced exodus imposed on the Palestinian people between the years 1946 and 1948, rooted people much more to their land.

I think that when you listen to people like my father, his testimony, you hear about the land, about being rooted to the land.

Some Palestinian people are still waiting to go back to their homes, who have the deeds to their houses. But I don’t speak about rootedness in those terms. I speak about rootedness to the land, to the territory, with all that this means. Why is there a conflict in this place and not anywhere else? Well, because of the symbolic value of Jerusalem, claimed by the three monotheistic religions. It seems that today, even though we are supposed to be a product of scientific thinking, we still believe that the power lies within these places as a source more magical-religious than anything else. It’s very interesting.

So, I think that this rootedness, which, from my point of view, is linked to territory, to land, to production, is like a response to the most absolute dispossession that the Palestinians have suffered since 1948.

ii. Palestinian Destinations

Let’s talk about ’48, which is when people flee their homes. Let’s talk about ’48, when people start, generation after generation, to become refugees. That is not a reality that we Costa Ricans can understand. I think a Nicaraguan can understand it. But a Costa Rican person of the 20th and 21st centuries needs help to grasp it.

We were in Lebanon in July 2023. We wanted, as a family, to somehow support Palestinians on behalf of my father, who was no longer with us. In Lebanon, there is an impressive number of Palestinian refugees. In the south of Lebanon, in Sidon, the Palestinian authority has a hospital and a lot of support forces for Palestinians and for Palestinian refugees.

Before going to Sidon, we went to the Palestinian Embassy in Beirut. We were received by the ambassador. Aside from him, in the ambassador’s office, we met the leader of the women’s groups, two doctors, and many other people. Everyone was a refugee, everyone. There was not a single person who was not a refugee.

I am Palestinian. We are Palestinians, and that was instilled in us by my father. I have 52 years of being Palestinian, of living the conflict, of suffering the conflict, of feeling the impotence that any Palestinian feels. Yet it was not until that moment that I realized that “being Palestinian” is not “one Palestinian being.” There are “several Palestinian beings.” I don’t think they are ways of being Palestinian. I am Palestinian from a reality of absolute freedom within absolute freedoms that do not exist. And this is because my grandfather decided not to travel to the north, but to cross the Jordan River and go to Jordan. Because the doctors we met in Beirut, their parents decided to go to Lebanon, and at that point they became refugees. In Lebanon, there was no assimilation or nationalization, like in Jordan and other countries. So, the decision that this doctor’s father made turned his children and grandchildren into refugees.

When my grandparents came with their children to Jordan, they were refugees, but that status didn’t last long. This was a way to have a safe place, some kind of support, and to start looking for work. That’s what I mean. There aren’t ways of being Palestinian, but destinations of being Palestinian. For me, this realization has been a reality check because one always has a notion of a huge population of Palestinian refugees. But somehow, I had not estimated how this is related or depends on the decisions they made, or the links that Palestinian people had at that time. The story that one of those doctors told us was that his father had some ties in Lebanon and, furthermore, that nobody believed —not even before the seven-day war broke out— that this could not be solved.

iii. Recognizing the Palestinian Territory

My sister Wajiha and I were the first people in my family to go to Palestine in 1990. We went to study Arabic at the University of Amman in Jordan. There were no diplomatic relations with Israel, but we inquired and got a permit from the Ministry of Interior. We were allowed to go with permission not to stamp our passports.

When we arrived in Jerusalem, we passed through, saw the walled city, and continued to Bethlehem. We tried to go to the place where my father was from. We didn’t have any information because, on top of it all, we had traveled without telling our family. We went to Jaffa, which is now like a suburb of Tel Aviv, but in the nineties, it was the town (maybe a little bit bigger) where my dad came from. The mix of people that my dad grew up with was even still there, of Arabs and local Jews, in which you don’t know who is what.

When we told my dad, he was proud of us. But it wasn’t until 2002 that he gathered the courage to make the same trip with my brother. They went to Jerusalem. From there, they took a bus to Jaffa. My brother says that “something” lit up inside my dad. He was only eight years old when he had to flee his home. My grandfather was in the Palestinian resistance, and his neighbor, who was Jewish, said to him: You are a target. My brother says that my dad walked through Jaffa and said not that minaret, that minaret. (The minaret is the mosque’s tower from where the Adan makes the call to prayer. Historically, he used to go up to pray. Today, it is done via loudspeakers)

He got there and said this is it. I am telling you this as if it were a fake story, but it is true. There was an old man who remembered the Sasa family.

In 2006, we made that same trip, this time four of the five children, and again four years later and with a major real estate transformation in the area. My dad went back to the same place. The mosque was still there, but there were no houses. The area had become a parking lot.

Just as I gave you those analogies of the za’atar, of the oil, of the olive tree, Palestine, being Palestinian, is linked to a territory. Definitely, because there is a debt of vindication to this place, of what the world has done to the Palestinian people, from those of us who have simply not said anything or have kept silent, from those who actually created the state of Israel by claiming some supposed rights that give Zionism the basis to be able to set up its own place, and from all the rulers who allow for every single UN resolution to be violated.

Today, in some places around the world, making a demonstration or pronouncing yourself in favor of a nation is censored. I believe that there is evidence here that indeed being Palestinian is linked to the territory. Then I would pose a question: is belonging to a religion linked to a territory?

Today, making a demonstration or pronouncing yourself in favor of a nation is censored in some places around the world. I believe that there is evidence here that indeed being Palestinian is linked to the territory. Then, I would pose a question: is belonging to a religion linked to a territory?

iv. Vindicating the territory

From my dad, I learned the importance of being tied to a territory. Throughout his adult life, my father demonstrated his rootedness, even though he could not have this in his own country. But the type of rootedness he has is that of a person who gives everything and brings everything to the place where he is. In Costa Rica, he became a Costa Rican citizen who will be remembered for supporting the Palestinian cause, for Islam. That also implies rootedness, a rootedness that has to do with involving people in these other realities, and bringing that rootedness to other territories. Somehow, he needed it because he could not have it in his own place.

It is an identity that always claims the territory because otherwise, what are you? Territory not only has to do with land, it has to do with culture. If we don’t do that, what are we left with? Not with a dad who was born in Palestine, but in a territory that was somewhat called Palestine at some point in history.

All the things one does are connected. The militancy linked to the Palestinian problem is reflected in my life in different ways, almost as a metaphor for the urban topics I am interested in and study. I’ve always been interested in internal borders. I’ve been interested in all those urban border zones where rights are blurred.

I have a monotheme on socio-spatial segregation, on urban fragmentation. These are problems that exist in our cities. You could say that it doesn’t have to do exactly with this issue of rootedness, but why is that what interests me? Why am I so against closed condominiums, against walls?

The issue of rootedness is an important thing right now. Israel has been bombing a tiny fenced-in territory for 60 days now. There is a wall on one side. There is a heavily guarded sea on the other, a north and a south without a way out. When Egypt opens the gates, Israel says: OK, let them open the gates so that they can leave. But there is only one way: for them to go, to leave, to disappear and vanish from that place that is theirs. Through the southern door or underneath the ground. There is no other alternative. What they want is to get rid of the people, with permission and complicity from all of us.

The Palestinian conflict is political. It is a conflict of territorial control, of ethnic cleansing because those people who are there and who have the right to be there because their parents, their grandparents, and their great-grandparents were there, they belong to that land and they have roots. The only way for Israel to succeed is to open the southern gate or bury them.

I think there are a lot of imprints, some more subtle than others, of everything my dad said. I would interpret his rootedness in those struggles that he made public. Even the creation of the first mosque in this country is his work. Omar’s mosque is on the exact border between Calle Blancos and Montelimar (San Jose). Omar’s mosque belongs to the Sunni Muslim Cultural Association of Costa Rica. There are quite a few Palestinian families in Costa Rica.

Concerning conflicts, they touch you. Although I know that I am privileged, and that I have never lacked absolutely anything, I am the daughter of a child who had to drink the urine of his younger siblings while they were running away. So, I had that dad. I listened to many of his stories, and they have shaped a lot of my identity. Israel does acts of this type periodically. Never with the ferocity of this one, but the attacks against the territories and the Palestinian people are periodic and almost cyclical. Every time I see these things and understand myself from a distant position, embodied by my destiny, by my reality, impotence overwhelms me.

v. What can be done?

This rootedness begins to play a leading role because it is more than rootedness; it is to understand that to be Palestinian is to be linked to a territory. And that the territory also makes that Palestinian being. These could be the ways of being Palestinian. The lives of all those women, children, and men, we have to humanize all the people who have died. To those, we can give a name, a surname, a history, and a life.

Indeed, there are many ways of being Palestinian. For some of us who are here, the only thing we can do is talk to those who want to listen, tell them, try to make people understand that the conflict is not a religious conflict.

We have to write a lot, talk to people. In this world dominated by Zionist capital and where the media presents distorted truths, I try to make this define me on a personal level. People don’t give meaning to it or understand what is going on. But today, with more than two months of having this mediatic genocide, the lack of outrage is incomprehensible.