Border Negotiations

by: Paula Piedra

Free Palestine, Palestine, solidarity

In 2018, for the fourth consecutive time, I had the opportunity to attend the annual assembly of Arts Collaboratory (AC). The hosts of this assembly were the organizations: Ashkal Alwan (Beirut, Lebanon); Al Ma’mal (East Jerusalem, Palestine) and Riwaq (Ramallah, Palestine). The idea of holding this gathering in the Middle East had been in the works for years. In 2016, the plan was to have the meeting in Lebanon, but since it was impossible for members of Palestinian organizations to be admitted to that country, the event was moved to another location. So, for 2018 the proposal was as follows: half of the members of the network would travel to Lebanon, the other half to Palestine and, at the end, we would all meet in Jordan, a territory, that we might say is neutral for Palestinians. I chose the combination of Palestine and Jordan.

I arrived on June 20, 2018 in Tel Aviv late at night, after 21 hours of travel. Aline picked me up at Ben Gurion Airport and drove her car for more than an hour to her house in East Jerusalem. Next day, I had breakfast with Aline and her mother. They served me homemade bread, zatta, olive oil, cucumbers, watermelon and instant coffee. We went out to buy fruit for the snacks of the coming days. Aline strayed from the path to show me a refugee camp, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the view of this city from the Mount of Olives. We arrived at the Jaffa Gate, on the perimeter of the old walled city of Jerusalem. Some girls from Al Ma’mal, the private foundation devoted to contemporary art to which Aline belongs, were waiting for us and received the fruits. Aline and I drove quite a while to leave the car in a parking lot and enter through the New Gate, another entrance to the old city of Jerusalem, completely gentrified and full of tourist attractions. That day I remember being in Al Ma’mal, hearing its story, going out to eat falafel with Aline, running into many Orthodox Jewish boys. I remember especially one who looked at me and instantly blew his face against the wind to avoid meeting my gaze. That night, I went to bed early and at 3:00 a.m. I was awakened by the Muslim chants that immediately became the soundtrack of a merciless jetlag that kept me up all that cool night.

The assembly officially began on June 23. So, I still had one day to adjust my schedule and see a bit of the ancient city of Jerusalem. I settled in the hotel located inside the old city. Then, I went for a walk alone, along the perimeter marked by the city’s ancient walls. From Jaffa Gate, I went to the Armenian Quarter and left through Zion town gate, following a sign that led to the location of David’s last supper and tomb, as well as the church erected on the site where Mary is said to have died. I entered again through Zion gate and into the Jewish Quarter, by chance finding the Wailing Wall. There, I was asked to cover my shoulders. I wanted to approach the wall, and unknowingly started down the men’s side, but soon three men corrected me, and I went to the other side. That is when I noticed that, on this wall, there is a side for men and another one for women; and the women’s side is smaller than the men’s. From there I went to the Muslim Quarter. I was unable to go to the Dome of the Rock: for security reasons, you can only visit at certain times. Then I went to the Christian Quarter. I went inside the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. I saw many people worshiping and throwing themselves on the stone slab indicating the tomb of Jesus Christ, and weeping. Later, I was struck by a shop where you could have your picture taken with biblical passages in the background. After all this, I got the feeling of having been walking through different stories, as if I were inside a theme park of the monotheistic religions of our civilization.

The days would pass between visiting those cities, art centers, and meetings facilitated by Maria and Eirini, two Greek women from the organization “Art of Hosting,” who would assist us in our conversational processes to help us tackle the easy and difficult issues with the intent of confronting them and reaching agreements.

On the first day of the assembly, we met Daoud, a member of another Palestinian art organization, who offered to give us a walking and talking tour of the old city. His first question still resonates in my head. “Which Jerusalem are we talking about? Because every stone in this city has its own story,” he said defiantly. Daoud told us about the geopolitical complexities; he used some phrases like: the puzzle of Jerusalem; a continuous catastrophe; occupying the territories is a business; solving the Jewish problem in Europe; King David is a legend; who controls the land? He made it clear that whoever is in power can take ownership of a territory through the narrative they build about it. With Daoud, I went back to the different neighborhoods, only now I had his expert vision, which told us: “Why is there a mosque in the Christian Quarter? Why is there a mosque in the Jewish Quarter?” When going through a Syrian Orthodox church to go to the Jewish Quarter, Daoud’s phrases I recall are: the purpose of dividing neighborhoods is to create conflict between religions; a strategy that works; the problem is related to territory and control, not religion; the city was not divided before −there were no boundaries or fixed borders; peace is building a mosaic as a symbol of everyone living together; our struggle is to recover that memory.

With Daoud we also visited a hoash, the Arabic word for courtyard. It is a type of ancient residential organization where each family shares one room and all these rooms face a central courtyard. What Daoud wanted to show us is how the Israeli occupation works. The strategy is to begin fragmenting these homes by placing an Israeli settler in one of the rooms. In addition, such occupants are switched around regularly, which means their rooms are neglected as compared to those with Palestinian families. There is also a heavy security system of surveillance cameras that inhibit the lives of local inhabitants.

*

A documentary by Issa Freij in 2006, called “Last Supper (Abu Dis)”, narrates the experience of some Palestinian inhabitants of the town of Abu Dis, located on the outskirts of Jerusalem, while their houses are being surrounded by the wall built by the Israeli government, as an alleged security measure. The film clearly exposes the human rights violation and the strategies of fragmentation, colonization, and subjugation of the Israeli government upon the Palestinian dwellers.

*

To visit the West Bank was to go through military posts warning, in large red signs, that you are entering the Palestinian side. It was also to experience Israeli soldiers getting up on our minibus to check each of our passports with great scrutiny. We also learned that some Palestinians, depending on their identification (there are 4 categories), cannot enter Jerusalem or need special permits to do so. They cannot even go to certain areas of the territories grouped under the name of the West Bank. We understood how this physically separates entire families, but above all it undermines the oneness of what we call building community. It cripples the possibility of reunion, and therefore works to weaken and dominate.

Hebron, located only 35 km south of Jerusalem, is the second largest city in the West Bank. It presumably hosts the tomb of Abraham, so it is sacred land for the Muslim, Christian, and Jewish religions. It once was an important economic, social and cultural center, though today it is known mostly as a ghost town, due to the negative impact of the occupation and its separation or segregation policies, which violate the human rights of thousands of Palestinians to protect the Israeli occupants of this city and its surroundings. This system of separation that has been installed in Hebron has forced many Palestinians to leave their own homes.

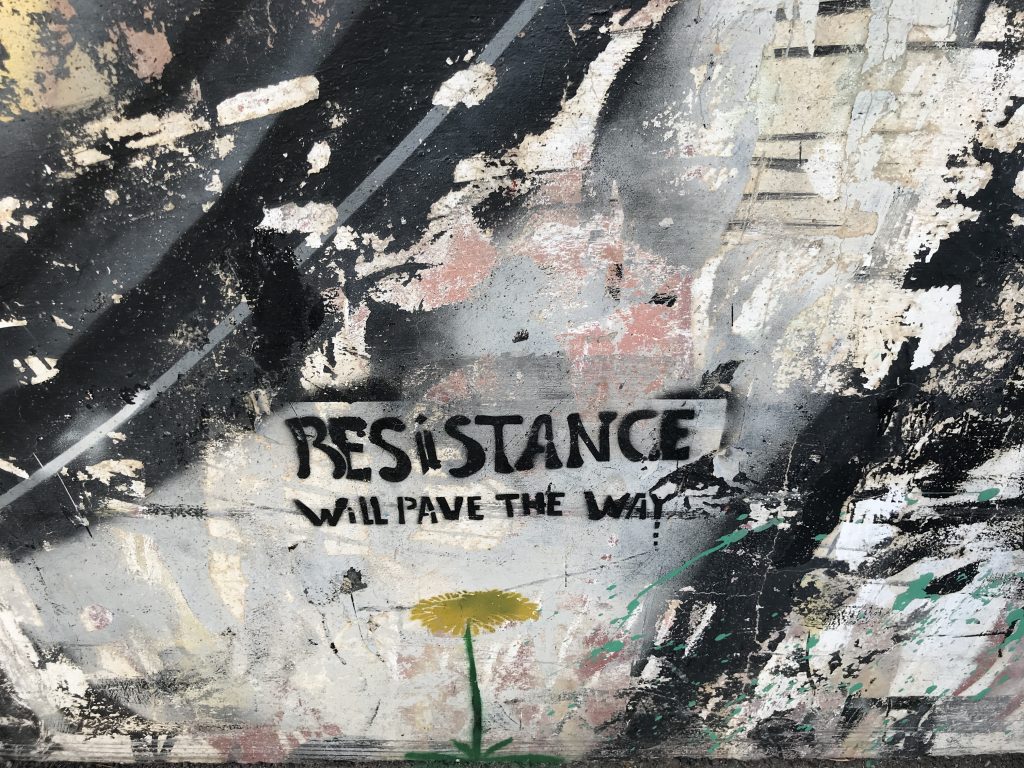

We visited the space that houses the organization called YAS (Youth Against Settlements). To get there, we had to navigate the military post on Shuhada Street, where two of our Palestinian hosts could not get through. We crossed it feeling dismayed at seeing them on the other side of the fence, and we wandered down empty and dusty streets to get to another military post where, after many questions, we were not allowed to keep going. Even so, our Palestinian hosts taught us that when they come up against a barrier, they stop just to think about other ways to get where they want to go. That’s how we turned around and started to climb some dry and dusty hills that stand firm in the sun, full of ancient olive trees. We arrived at the headquarters of YAS, a group of non-violent activists seeking to end the construction and expansion of illegal Israeli settlements through non-violent popular struggle and civil resistance.

Both Murad Amer and Muhanad Qafisheh told us about their personal experiences and how, to protect the illegal settlers, the Israeli state systematically imposes a regime of forced evictions, curfews, closures of streets and markets, military checkpoints, frequent random searches, and arrests without charges, as well as turning a blind eye to the unrestrained violence of the settlers against the Palestinians.

As we left YAS, we reunited with our friends who were waiting for us on the other side of the military post, and we walked to Hebron Rehabilitation Committee, who have dedicated themselves to revitalizing the life of the ancient city of Hebron, renovating historic buildings, as well as encouraging Palestinians to return to live there. To date, around 1,300 apartments have been restored and almost 7,000 people have returned to the ancient city of Hebron. Not only do they renovate old buildings; they also rehabilitate the city’s infrastructure: streets, schools, and other services. Their legal department provides assistance recording and documenting violations of the Israeli state on the Palestinian population.

From Hebron we went to the city of Dahrieh. When leaving the Municipality of this city, I recognized something that I had already seen in the craft market of Hebron. It was a sign made of ceramic tiles, imitating traditional Palestinian tiles, which reads −both in Arabic and in English− “Jerusalem,” and states the distance in kilometers from its location to the city of Jerusalem. I asked what it was, and that is how I learned about this work by Palestinian artist Khaled Houran, entitled Ramallah: The Road to Jerusalem, of the year 2009. Khaled has installed the tiles in different points of the Palestinian territories under occupation. They display the physical distance to a territory not all Palestinians can reach (Jerusalem), though most of the time they serve as a cue that hints less at the actual physical distance (because sometimes it is ludicrous) and more at a metaphor for how distant the policies of exclusion and the neoliberal, colonial, and imperial challenges imposed by the Israeli occupation in Jerusalem and its Palestinian inhabitants are from rationality and humaneness.

How do networks operate, and what are they for? We met at the Al Hoash art center to talk about this. Both they and Al Ma’mal are part of the Art Network of Jerusalem “SHAFAQ,” and jointly organize a series of events with the purpose of reactivating cooperation and supporting life and Palestinian resilience in Jerusalem.

Reflections within AC revolved around these questions: What does it mean to have a support network? What is our common vision or purpose? Where are we going as a network? The most significant phrases that I take away from that meeting are: in a network, it is more feasible to face challenges; instead of being one, being a movement; networks create presence and unity, the opposite of fragmentation and invisibility; gathering in recognizing our need for the other.

*

On June 26, we left our hotel in the ancient city of Jerusalem and went to Ramallah. This is the city that hosts Riwaq, who have spent the last 28 years preserving Palestinian collective memory through projects that document and restore architectural heritage sites in the West Bank and Gaza. It is a team mostly made up of architects with expertise in restoration and landscaping, who undertake joint efforts with the communities to recover their memory and somehow reclaim their existence and permanence in these territories. Ramallah is part of “Territory A,” i.e. despite being under Palestinian control, the area is under Israeli military occupation, and Israel could intervene at any time. Ramallah is the de facto capital of Palestine, and seat of the provisional government of the PNA (Palestinian National Authority), which claims an independent Palestine and for East Jerusalem to be its capital city. (It is currently annexed and proclaimed as part of the Israeli capital.)

Meeting Yazan Khalili, director of Khalil Sakakini Cultural Center, was one of the most stimulating experiences. The center is going through a moment of reflection by testing a management model that seeks to revitalize its activities, not only by rethinking its programming and audience, but also by trying more collaborative and sustainable forms of production and management that involve the center’s engagement with the community and vice versa, in order to build a structure based on solidarity.

The last stop that day was in PYALARA (Palestinian Youth Association for Leadership and Rights Activation), an association that works with young Palestinians between 13 and 25 years of age to strengthen their leadership skills and support them in developing projects based on their own needs and rights, so they may have tools to adapt to their contextual situation, as well as confidence and hope to build a democratic society.

Today I looked for an individual seat on the minibus, so I could get lost gazing into the arid desert landscape on the way to Qalandiya and think about why I was seeing these realities. I felt deeply saddened, and suddenly found other types of violence, indifference, and fragmentation in my own life. For example, I thought about my own family unit, how it was impossible to communicate with my parents. I remembered the negotiations in my youth to defend my passing from mother’s territory to father’s territory, and vice versa. I asked myself: Where does violence begin? And fragmentation? Indifference towards the other?

*

The last day in Ramallah, June 28, we went to Birzeit, directly to the Palestine Museum. After seeing the temporary exhibition, we had a long work session facilitated by our friends from Art of Hosting. It was a nurturing conversation that reflected upon understanding ourselves as living systems, and not separate machines, and on the importance of creating spaces to listen and converse with intention.

Of everything we talked about, what most impressed me was the possibility of learning to be in the space between knowing and not knowing, a space between chaos and order that is precisely the right place for creativity. The metaphor is that systems located wholly on the side of order lead to death. For example, the system of Israeli occupation and control over the Palestinian territories. Likewise, on the other side of the spectrum, complete chaos is also equivalent to death. How to situate oneself in that intersection between chaos and order, where there is a framework or a foundation to sustain and help generate the conditions for creativity, renewal, and transformation to arise from a bit of disorder? The paradox is ever present; art emerges in this tension.

The last stop before leaving Ramallah was the opening of the AM Qattan Foundation and my encounter with The Pomegranate by Palestinian artist Jumana Emil Abboud. I freely recall some parts of The Pomegranate’s description (2005):

“… the hands of the artist… meticulously attempting to return pomegranate seeds… back into the pomegranate’s shell… this simple act questions the meaning of returning something in order to restore balance, but one knows the impossibility of such a task and/or dream. The act of trying to fit the seeds where they supposedly belong becomes an act of chaos. It is ritualistic and obsessive… the seed does not always fit perfectly … The seeds are displaced; their displacement is to be found in the fact that they exist outside of their skin (nest, home, nature), and also in the hope of a perfect return and the danger of an irregular placement … “

We took a bus to the Allenby bridge to cross to Amman, Jordan. By then, our Palestinian hosts Aline, Carol, Shata and Khaldun, had taken two different routes to cross from different points, as required by the Israeli state according to their identification documents. The only Palestinian hostess who was with us during this border crossing was Renad. She guided us gracefully from side to side, complying with all security requirements and other bureaucratic transactions. It was evident that, although we were passing different Palestinian and Jordanian military posts, really the whole operation is controlled by the Israeli government. By this I mean that there is an air of intimidation and suspicion towards any differences. Additionally, though it may seem unthinkable in the 21st century, some checkpoints and even buses are exclusively for Palestinians. This can only be called segregation.

*

In Amman, we finally had the assembly in full. It was almost like two rivers rushing to the sea: those of us who went to Palestine and those who went to Lebanon, each one with quite different prior experiences, now mixing together in effusive greetings. Affection is an important part of the backbone that undergirds the AC network.

The three days of the meeting in Amman were hosted by Darat al Funun, a private, non-profit organization devoted to the exhibition and research of contemporary art. Those three days, work sessions focused on agreeing on a series of decisions to clarify which working groups would remain in force, plus other decisions about our administration and internal communication. Likewise, after several sessions following participatory methodologies, the AC assembly defined its vision: “The purpose of Arts Collaboratory is to reimagine and generate ways of life, both locally and globally, through collective artistic practices”

*

The last thing I want to mention is my return home. First, my naive misunderstanding of my hosts’ suggestion of returning to my country leaving Jordan. In my practical mind, I did the math: It is easier and cheaper to buy a round trip ticket between two places: San José – Tel Aviv. But my brain had not really grasped where I was going. These realities can become so alien to us that we cannot even fathom them. I can now say I experienced first-hand (albeit in the lightest, least painful way, and only for a few minutes) processes of interrogation and intimidating scrutiny simply for being suspicious of having been with the “others.” I am not trying to sound very knowledgeable, but this has given me a slightly more rounded perception of the world we cohabit.

Upon returning to Costa Rica after these travel experiences, I wrote each of the interrogation dialogues I had with Israeli officers, both on the border with Jordan and at Ben Gurion Airport. The structure of all of them is similar: asking a series of questions and systematically repeating them again and again, randomly, either so that you finally admit to what they suspect (that you were with Palestinians or visited Palestinian territories), or so that you yourself begin to suspect that you did something terribly bad and confess that you were with Palestinians and visited their territories. In the end, it is about subjecting the suspect, instilling fear and, by association, leaving them indoctrinated or punished for breaking the principle of loyalty that establishes that it is treachery to interact with any Palestinian, because any one of them is the enemy.

*

Recently, Benjamin Netanyahu was re-elected (for the fifth time) as Prime Minister of Israel, despite facing charges of corruption. In his campaign he promised, among other equally threatening ideas, to annex to Israel many of the settlements that have been established in the West Bank illegally.

I know that art by itself cannot change society, its politics or its economy, or anything. But what would happen if we did not even have spaces to imagine other ways of relating through creative practices? Art can promote experiences that attempt to propose other policies and other economies −based on affection− with the common goal of building life-centered, nurturing support structures.

My experience in each organization I visited, with each person I met on this trip and at this assembly, is precisely related to thinking about supportive systems and developing strategies of community resistance and resilience. With that purpose, personal action is the basis to help weave this type of tapestry. I came back with the awareness that individual borders keep replicating themselves, in a form of contagion, reaching collective boundaries that later materialize in territories, systems, and ideologies. In knowing our own borders −the ones we have chosen, and the ones imposed upon us−, we have the possibility of learning to negotiate them (or not). In a way, it is what makes our individuality capable of existing with other individualities in the different collectives in which our lives unfold.

San José, May 5, 2019.