The making of solidarity has the verb “action”

by: Georgina Faun

Collaborations, Georgina Faun, solidarity

by: Georgina Faun

Collaborations, Georgina Faun, solidarityFor example, the word “work,” so often utilized and valued in our endeavours, has an etymological relationship to tripalium, a torture instrument used on slaves. At the same time, so many other words begin to shed the strength of their existence, or are stripped of their emancipatory character to nurture the present world that rejects them. It is here where I place the word “solidarity,” one of many caught in between the dispute of preserving its essence, or getting recycled by the language of capitalist domination.

So here I am

I am still lost in the face of losing myself

the pain of this heart that looks around

and protests with an alien beating

The heartbeats that make me throb

mirrors where I look at myself

say things about me

and of others that could be me

So here I am

Looking at the insides

scraping the entrails

to expel the bile

and become stronger

in the filth

Etymologically, the word solidarity connotes an action: that of someone who wishes to be solidary. It comes from the latin solidus, which could be understood as solid or firm. At the same time, solidus contains the prefix “sol,” the name of the Sun, one of the most important celestial beings that in Latin refers to what is complete. Therefore, solidarity can only be conceived from the action of it: “to make solidarity,” to contribute to the strengthening of something. The quandary then lies in the “something:” in what we aim to strengthen and what motivates us to participate in it.

I think of the moment that my vocabulary was conferred with the word “solidarity,” when I began using it instead of “support” or “help.” It takes me back fifteen years, when the Mexican state charged at us with repression and every step of rebellion was repelled with the threat of disappearing, death, or jail.

To put solidarity into action has allowed us to be present in difficult moments, but also to participate in the changes that we bet on and to abandon the comfort of just letting life go by.

Parenthesis: it is not that this scenario is any different from nowadays, but it is important to say that in my story, it is, because it is in this place, turned into the land of mass graves, disappearances, abductions, state murders, femicides, and arbitrary incarceration, where solidarity becomes one of the primary weapons to resist and face those in power.

The word solidarity appeared not only to nurture the lexicon of our conversations; it became a common practice and a bet on the immediate transformation of our survival. To put solidarity into action has allowed us to be present in difficult moments, but also to participate in the changes that we bet on and to abandon the comfort of just letting life go by. Solidarity becomes that sharp weapon that makes an invisible network tangible.

My restlessness as a historian led me to ask myself about the need for networks of solidarity within social movements which, just like us, had to face the state as this great leviathan that needs to be destroyed.

When some of our partners were in prison, a network of kinship came together to make a solidarity group. To sustain those who were in prison and fight for their freedom —even with the contradictions that this entails—was a task that led us to face breakups and rifts with people who at some point had been close. In an attempt to give myself some sense of purpose, I asked myself how solidarity networks had worked in other times, aiming to show their importance and the need for them to exist.

I arrived at stories of covertness and discovered the almost nonexistent possibility of “historicizing” those networks that allowed for many lives to not fade away. How do you ask archives about the invisible hands? What clues can we track down to manage this? How do we create history about what is not written down or accounted for? That is where I found the following. 1

A newspaper article gave me information on a man who escaped from a Spanish prison in 1982. Accused of being part of an armed group, he would have faced a sentence of more than thirty years incarcerated. A network of people thought up the first step and executed it: to get out of prison only to later lose track of them.

I consulted the largest amount of newspapers the library allowed me access to in search of a trace of the protagonist of this story. With enlightened, stupid selfishness I regretted not being able to find anything else, an indication that the man was never aprehended or found again. Due to the proximity of this story —it had happened less than forty years ago— I began to ask myself if my genuine interest could not entail some danger. I opted to look for actors of that time that could tell me “something” about that episode. In my search, I was able to envision a network of people that, both in Europe and in America, had weaved a silent structure for many people to escape from prison or death just like that fugitive, and reinvent themselves in other places, thousands of kilometers away. These people, whose names will perhaps never be written in any book, acted in solidarity, honoring life in the face of state repression. With their silent actions, they strengthened the armed resistance and the fight against power, making the cry for freedom their own.

This brief story is one of the examples I can refer to nowadays when we talk about solidarity. So, I come back to the question: What do we strengthen? What do we stand in solidarity with? To which I almost immediately can respond: we stand in solidarity with our equals, who in multiple ways resonate in our path, we create kinship with other geographies, and vindicate solidarity through defending it as our prefered weapon to strengthen the life that is taken from us.

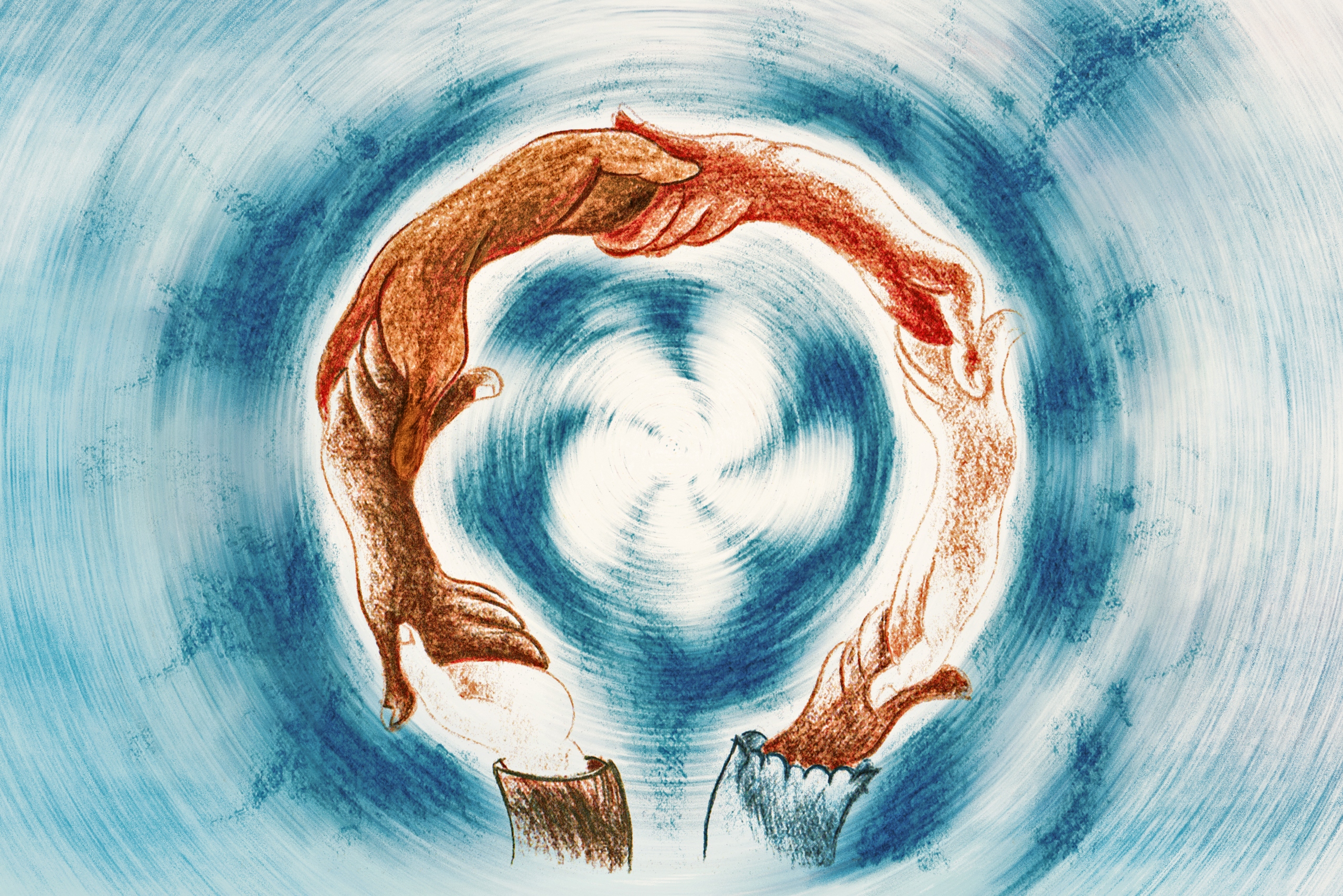

Image by: Erik Tlaseca

Translation: Lola Malavasi Lachner