Esquizos (2021-2023)

by: Dulce Chacón Nicolás Pradilla

Drawing, Quelites

Translated by Lola Malavasi

Interview with Mexican artist Dulce Chacón

Dulce Chacón (DC): The series Esquizos takes its name from the black-and-white drawings of Francisco Hernández. As Philip II’s personal physician, Francisco undertook the first mission to identify the natural wealth of New Spain, commissioned by the Spanish Crown in 1571. He spent seven years in the region conducting a botanical survey. The purpose was to exploit it economically for the benefit of the Spanish crown. He gathered a group of informants composed of traditional doctors, herbalists, and shamans, who provided him with much information on medicinal and nutritional uses.

The result of this expedition was a series of color drawings made by tlacuilos. These drawings were sent to Spain in books later kept in the Escorial library, which suffered a great fire in 1651. The volumes and many other documents were lost; the only remaining drawings are the black-and-white versions that Hernández kept with him.

I revisit this history to make the Esquizos series as part of a process of artistic research based on knowledge of Mexico City’s plants that I inherited from my mother and grandmother.

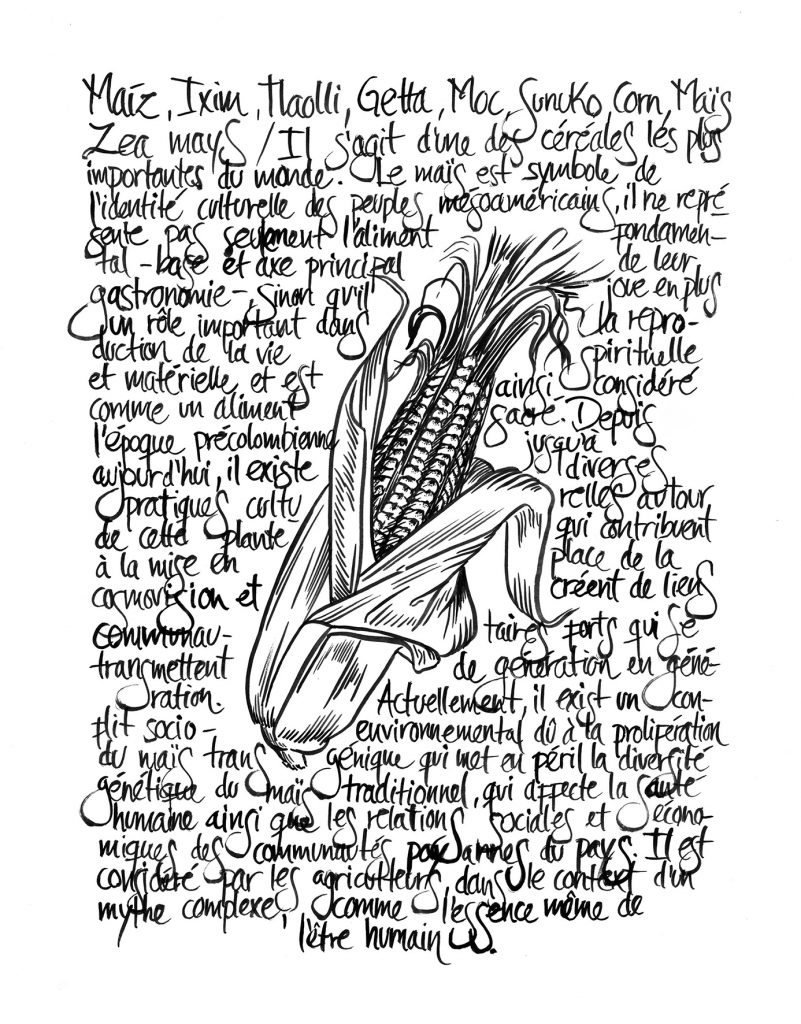

In 2019, I took a certificate course in scientific illustration in which I focused on the botany of agave species (Agavaceae), specifically those used to make mezcal. By understanding scientific illustration as a language within drawing, focusing on the descriptive nature of morphological features, I realized how normative scientific language is. In that sense, I describe some properties in the Esquizos series —food, medicinal, and ritual properties, as well as the ecosystems in which each plant interacts— through calligraphy and images of the plants. Each drawing is a record of a personal recognition of the species. In that sense, it is a project of self-exploration.

Nicolás Pradilla (NP): Those who informed Francisco Hernández generated defense mechanisms by recognizing the instrumental reason behind his interest in botanical knowledge. Your project aims to divulge this but also question the co-optation surrounding these plants, the role of which is central in the biocultural horizons of different peoples of the region. Can you elaborate on this relationship between showing something and not showing it?

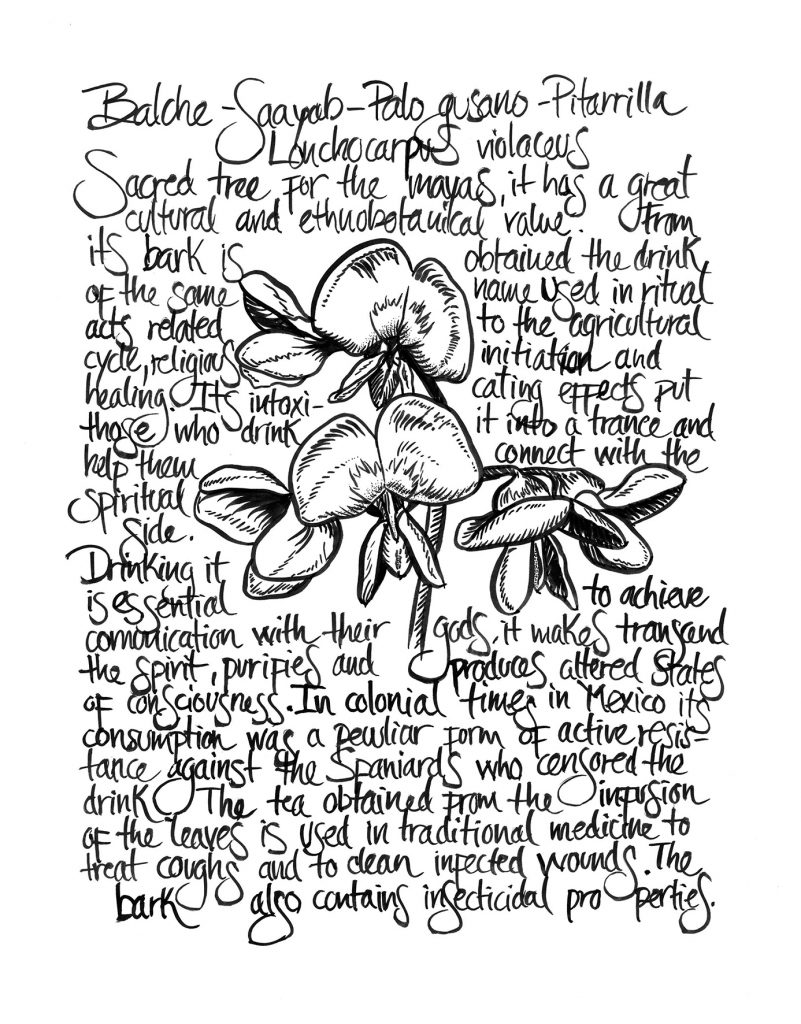

DC: They were not just his informants. The people soon realized how the colonizers instrumentalized and demonized the knowledge of the uses of certain plants related to religious practices, which resulted in censorship from the Spanish Crown. A classic case is amaranth, censored because of its use in making tzoalli, figurines that represented various deities, created by mixing the amaranth seed with maguey honey and the blood of sacrificial victims. These rituals, considered “pagan” by the Catholic religion, were rejected, and the plant was forbidden. This was also the case with balché and many other plants related to religious rituals and the agricultural cycle. The people quickly recognized the importance of not revealing certain practices to prevent the associated plants from being prohibited. In the case of amaranth, the prohibition had a profoundly dramatic impact since it has a lot of vegetable protein. Its censorship during the colonial period caused considerable nutritional detriment to the population that contributed to a higher mortality rate during the smallpox and measles pandemics of the 16th century. The prohibitions eroded the cosmovision but also the health of the population. Therefore, the inhabitants began to keep many practices related to plants out of sight.

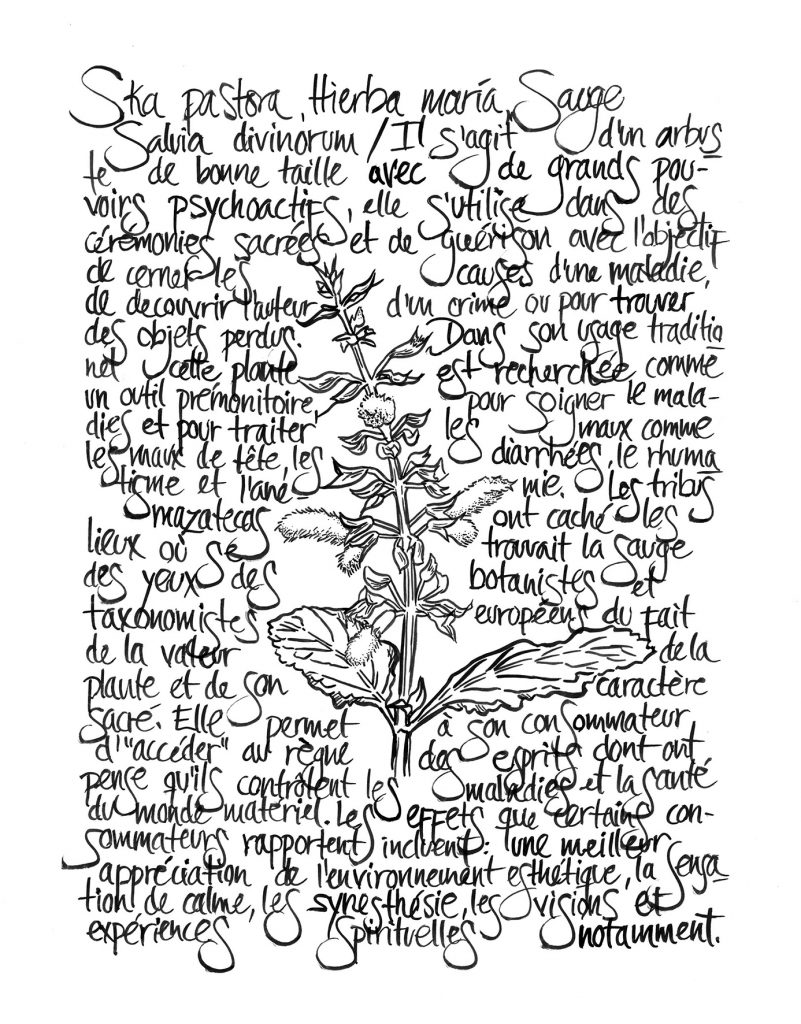

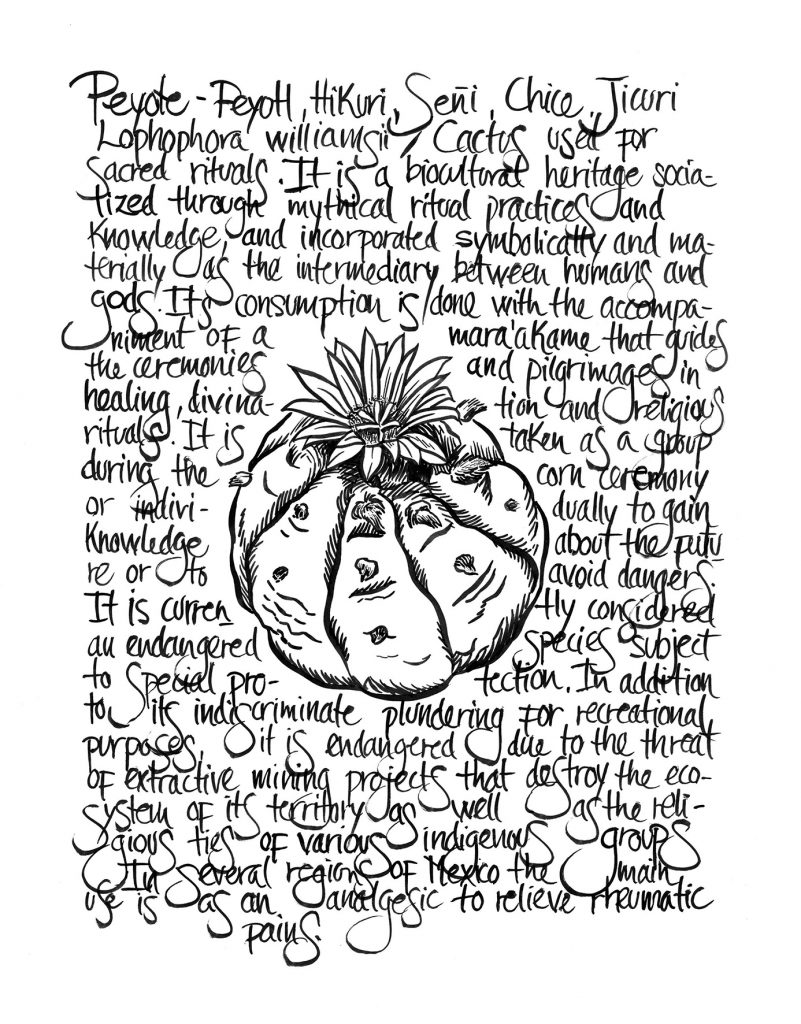

Through researching quelites such as amaranth, purslane, papalo, salvia divinorum, balché, or even corn and peyote, I learned there were many associated practices hidden from the Spaniards. For example, kernels of the corn are used for divination practices that have been kept hidden.

After briefly reviewing the characteristics of certain native plants, I revised specialized historical, sociological, and anthropological literature to learn more about their nutritional, medicinal, and ritual uses. Based on this, I edited this information to include it in each drawing. In this way, each one has nutritional, pharmacological, symbolic, and ritual information on the uses of the different species.

NP: Thinking about what is revealed and what is safeguarded, from your practice as an artist, do you think any strategies can be implemented to resist the persistent mechanisms of knowledge capture?

DC: At the beginning of the project, I asked myself what information to include or leave out. In addition to the space restriction within the drawing, I questioned the perspective from where I was reading this information. I began a self-exploration about access to knowledge on plants, traditional family uses, and where they come from. From there, I assessed the relevance of sharing the knowledge I get from other sources and inherited from my family. I evaluated the place of enunciation by recognizing myself as a woman, a contemporary artist, who lives in Mexico City and has access to certain knowledge. I am not a biologist or a botanist. I am an artist whose main language is drawing, which I consider a tool for dissemination, but also self-exploration based on what I have inherited and continue to cultivate. The drawings are the result of an editing of the information I have access to, having in mind what needs to be said or not. For example, I found many recipes of types of religious, dietary, and medicinal uses that I thought were irresponsible to include in the drawings because I do not have the knowledge to do so. Some can be very toxic if not used properly. There is some information that I cannot reveal.